India’s Laptop Import Restrictions: Right Path or Risky Gamble?

The Government of India announced import restrictions on laptops, tablets, all-in-one PCs, ultra-small form factor computers, and servers on August 3, 2023. According to the government’s directive, these products can now only be imported with a valid license for restricted imports. However, the implementation of these restrictions has been deferred to November 1, 2023, providing some breathing room for stakeholders.

This move aims to promote local manufacturing of products included in the recently renewed PLI scheme for IT hardware. IBT takes a closer look at the rationale behind the bill, and India’s readiness to actually shift manufacturing of these devices within the country.

Image source: Pixabay

On August 3, the central government imposed restrictions on the import of laptops, tablets, all-in-one computers, ultra-small computers, and servers, with imports only being allowed for those holding a valid licence for restricted imports. The trader should have to be a regular importer to get a license. The restrictions have been imposed under HS Code 8471 (Data processing machines) on seven categories of electronic gadgets.

Under the transition provisions of the foreign trade policy (FTP), if the bill of lading and letter of credit has been issued or opened before August 3, the import consignments can be imported. The government expects import licensing to encourage local manufacturing, with the production-linked incentive (PLI) scheme for IT hardware acting as a sweetener.

Exemptions have also been given for import of one laptop, tablet, all-in-one personal computer or ultra-small form factor computer, including those purchased from e-commerce portals through post or courier. Exemption from seeking import licensing for up to 20 items per consignment for R&D, testing, benchmarking and evaluation, repair and return, and product development purposes. However, these imports shall be subject to payment of duty as applicable.

Before import restrictions take effect on November 1, 2023, manufacturers including Apple, HP, Lenovo, Dell, Asus, and Xiaomi are working to get as many laptops and tablets into the country as they can. To make sure there is enough pipeline stock for 4-6 months when the new licencing regime for imports of laptops, tablets, and personal computers begins, these companies will increase imports by up to 50% more than what they had initially planned until the end of October.

Shortly after the announcement, shares of local electronics contract manufacturers rose. Amber Enterprises India Ltd. gained as much as 3.3%, Dixon Technologies India Ltd. rose 5.5% and PG Electroplast Ltd. spiked 2.8%, reported Bloomberg. Netweb, a domestic server manufacturing company, also saw its shares going up 4% along with Dixon Technologies (approximately 8%).

The government of India is open for granting foreign companies more time to establish manufacturing units, given they provide detailed “Make-in-India” plans for specific products like laptops and servers. These companies are seeking up to a year to set up local factories. Successful plans could lead to relaxed import licensing norms, encouraging global giants like Apple and Dell to manufacture in India, moving beyond contract manufacturing.

Local manufacturing or data security?

The aim of this move is largely being seen as a push for India’s ‘Made in India’ scheme and a bid to reduce dependencies on China. However, there are a variety of reasons for imposing these restrictions. The primary stated reason is to ensure that the security of Indian citizens is fully safeguarded.

According to ICEA, there are other benefits of import restriction then reducing the dependency on China such as employment creation by way of 5 lakh additional jobs, adding 1.26% to India’s GDP by 2025, attracting a cumulative inflow of foreign exchange to the tune of US$ 75 billion, and investment of over US$ 1 billion, all of which may result in manufacturing value of US$ 100 billion.

A glance through trade data released by the Ministry of Commerce and Industry gives us a broad picture of India’s import dependence of electronic goods such as laptops, computers etc.

| India’s Laptop and Other Products Import Trends | |||||

| S.No. | HS Code | Commodity | 2021-2022 | 2022-2023 | %Growth |

| 1 | 84713010 | Personal computer | 7,370.85 | 5,336.18 | -27.6 |

| 2 | 84713090 | Othr dgtl automatc data-procesng machine | 583.76 | 553.14 | -5.24 |

| 3 | 84714110 | Micro computer/processor | 2.08 | 1.2 | -42.63 |

| 4 | 84714120 | Large/main frame computer | 0.46 | 0.16 | -64.69 |

| 5 | 84714190 | Othr dgtl automatc data-procesng machine | 100.28 | 179.16 | 78.65 |

| 6 | 84714900 | Othr digitl automatc dataprocesng machine | 125 | 136.06 | 8.85 |

| 7 | 84715000 | Digitl procesng units excl of sub hdngs | 2,199.26 | 2,579.84 | 17.3 |

Source: Ministry of Commerce and Industry

India’s imports of the electronic goods have been steadily rising. In 2019-20, they stood at US$ 5,352 million and further climbed to US$ 10,382 million in 2021-22, before declining slightly to US$ 8,785 million in 2022-23. This fiscal, between April and May, India has already imported US$ 1,200 million worth of these goods.

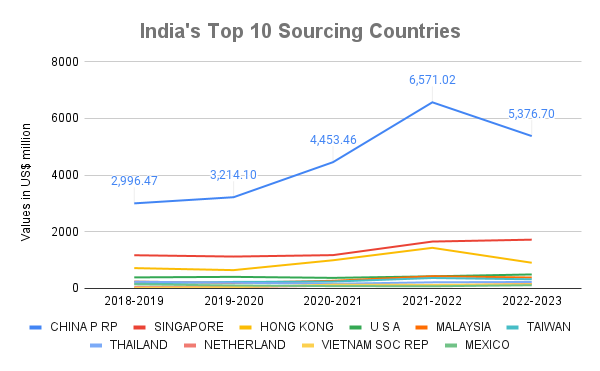

| India’s Top 10 Source Countries | ||||

| S.No. | Country / Region | Imported value in 2022-2023(US$ million) |

Annual growth | CAGR (2018-19 to 2022-23) |

| 1 | China P Rp | 5,376.70 | -18.18 | 15.74 |

| 2 | Singapore | 1,712.50 | 4.05 | 10.18 |

| 3 | Hong Kong | 896.35 | -37.05 | 6.14 |

| 4 | US | 482.61 | 16.18 | 6.29 |

| 5 | Malaysia | 373.43 | -10.74 | 13.07 |

| 6 | Taiwan | 311.1 | -12.66 | 18.26 |

| 7 | Thailand | 216.15 | 5.93 | -1.1 |

| 8 | Netherlands | 142.92 | 50.19 | 44.25 |

| 9 | Vietnam Soc. Republic | 134.76 | 17.87 | 109.02 |

| 10 | Mexico | 101.4 | 58.99 | -6.04 |

Source: Ministry of Commerce and Industry

Source: Ministry of Commerce and Industry

The country imported IT hardware products worth $8.8 billion in FY23, with China accounting for more than half at $5.3 billion, followed by $1.3 billion from Singapore.

| India’s Laptop and Other Products Export Trend | |||||

| S.No. | HSCode | Commodity | 2021-22 | 2022-23 | %Growth |

| 1 | 84713010 | Personal computer | 18.03 | 56.77 | 214.86 |

| 2 | 84713090 | Othr dgtl automatc data-procesng machine | 26.27 | 24.05 | -8.44 |

| 3 | 84714110 | Micro computer/processor | 0.3 | 0.51 | 71.29 |

| 4 | 84714120 | Large/main frame computer | 0.36 | 0.32 | -12.8 |

| 5 | 84714190 | Othr dgtl automatc data-procesng machine | 14.38 | 8.18 | -43.11 |

| 6 | 84714900 | Othr dgtl automatc data-procesng machine | 10.64 | 23.3 | 119.11 |

| 7 | 84715000 | Digitl procesng units excl of sub hdngs | 88.89 | 108.42 | 21.97 |

Source: Ministry of Commerce and Industry, Figures in US$ million

Exports on the other hand are quite miniscule, led by Digital processing units exc of subheadings at US$ 108.42 million, Personal computer at US$ 56.77 million and Other dgtl automatc data-procesng machine at US$ 24 million.

| India’s Top 10 Export Destinations | ||||

| S.No. | Country/ Region | Imported value in 2022-2023 | Annual growth | CAGR (2018-19 to 2022-23) |

| 1 | US | 62.75 | -11.27 | 26.07 |

| 2 | Russia | 50.85 | 203.71 | 109.49 |

| 3 | UAE | 35.89 | 45.29 | 4.24 |

| 4 | Singapore | 25.16 | 28.85 | 1.38 |

| 5 | China P Rp | 18.36 | 102.25 | 26.37 |

| 6 | Hong Kong | 15.15 | 372.25 | -4.34 |

| 7 | Netherlands | 13.38 | 73.78 | 42.55 |

| 8 | France | 8.65 | 180.4 | -8.35 |

| 9 | Bhutan | 6.93 | 16.86 | 35.43 |

| 10 | Bangladesh PR | 5.33 | -15.16 | 36.18 |

Source: Ministry of Commerce and Industry, Figures in US$ million

Is India ready for this development?

Experts believe that the decision will assist India in lowering its reliance on Chinese imports and strengthen its hardware supply chain. Further, it would help boost the economy by creating employment, build a robust electronics manufacturing industry and encourage more R&D. India will then be better equipped to serve a large global IT hardware market.

The global market for laptops and tablets alone is estimated at US$ 220 billion per year over the next five years. In India, the market size is estimated to continue to be around US$ 7 billion for the same period, according to International Data Corporation (IDC).

ICEA expects India to capture one-fourth market share of the global supply chain by 2025. The government’s import restrictions, effective from 1 November, are just a step in this direction. India is making progress in the laptop manufacturing sector, but challenges abound since India continues to import 87% of laptops and 63% of tablets, according to a joint report by the ICEA and consultancy firm EY.

The Indian electronics manufacturing sector is still relatively young, and there is a shortage of skilled workers with the knowledge and experience to manufacture laptops. Another challenge is the high cost of manufacturing in India. The cost of labor, land, and raw materials is all relatively high in India, which makes it more expensive to manufacture laptops there than in some other countries.

The government has introduced a number of policies to support the sector. The PLI scheme provides financial incentives to companies that manufacture laptops in India. This has led to a number of companies, such as Dell, HP, and Lenovo, setting up manufacturing plants. PLI Scheme 2.0 for IT hardware to enhance India’s manufacturing capabilities and enhance exports was introduced on May 17, 2023. PLI Scheme 2.0 is expected to result in widening and deepening of the manufacturing ecosystem by encouraging the localisation of components and sub-assemblies and allowing for a longer duration to develop the supply chain within the country. It was approved with a budgetary outlay of ₹ 17,000 crore (US$ 2.05 billion).

The Scheme will promote large scale manufacturing in Laptops, Tablets, All-in-One PCs, Servers and Ultra Small Form Factor devices and contribute significantly to achieve electronics manufacturing turnover of approximately US$ 300 billion by 2025-26. According to EY, even a 15% market share of laptops and tablets could rank among India’s top exports by 2025 given the estimated size of the US$ 220 billion annual global market. Additionally, according to UN Comtrade Data, India’s top trading partners include the US, European Union, Korea, Gulf Cooperation Council, Indonesia, and Switzerland.

According to Ajay Srivastava, founder of Global Trade Research Initiative, “The government’s recent initiative of laptop import restriction holds significant promise by providing a ready and receptive market for indigenous laptop manufacturers situated within the Indian landscape. This strategic maneuver not only bolsters the growth prospects of domestic laptop producers but also creates a transformative opportunity for achieving self-reliance. This move is particularly noteworthy for its potential to attenuate the prevailing import dependence on Chinese counterparts, thereby fostering a more resilient and diversified economic landscape.”

He further added, by mandating imports to transpire through regulated licenses, the government adeptly navigates the challenge of preserving the intricate web of supply chains that underpin the global trade dynamics. In essence, this initiative not only nurtures the growth of domestic industries but also serves as a blueprint for prudent and calculated economic maneuvering on the international stage.

The Future Ahead

India’s laptop import restrictions are a complex issue with multiple perspectives and implications. While national security and domestic manufacturing are important considerations, it is crucial to assess the impact on consumers, industry, trade relations, and the overall economy. Striking a balance between these factors is essential for effective policies that ensure both the security of the nation and the welfare of consumers and industry stakeholders. By considering alternative strategies and adapting to future developments, India can navigate laptop manufacturing successfully.

It appears to be a formidable challenge to develop into a major global export hub for electronics in general and for laptops, tablets, and desktop computers in particular. However, India has some advantages as well, such as the availability of labour at competitive wages, which makes it 80% less expensive than China in terms of GDP per capita, according to World Bank data, and a workforce that will likely be younger than China’s in the coming decades thanks to geopolitical factors, according to the International Labour Organisation. However, experts are indeed concerned whether India is ready for a shift of such magnitude.

Minister Rajeev Chandrashekhar has assured that this is not taking India back to the license raaj, but is rather aimed at building a trusted supply chain for India’s digital products. “In the three months that we have given to the industry, we are sitting down and working out a framework for how the government’s goals can be met, without disrupting what is the current growth and ambition of these companies,” he added. The coming months are expected to provide more clarity on how the government plans to achieve this balancing act.

The best write up on the subject..congratulations team