Vishwaguru Bharat: Examining India’s vision to become a higher education hub

India’s higher education landscape is characterized by a wide array of universities, colleges, and institutes offering diverse academic programs. However, despite its cultural richness, the system struggles to attain global recognition due to various factors.

To address these challenges and enhance its standing on the world stage, India has initiated programs such as Study in India and NEP 2020. IBT takes a look at the critical gaps and also discusses solutions and ongoing developments with a panel of expert academicians who critically dissect India’s progress towards its vision of becoming a higher education hub.

The higher education ecosystem in India comprises more than 1,000 universities and 42,000+ colleges depicting an enormous network. The Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs), the Indian Institute of Science (IISc), the National Institutes of Technology (NITs), Indian Institutes of Science Education and Research (IISERs) and the Indian Institutes of Management (IIMs) are some of the institutes that are furnished with state-of-the-art infrastructure, modern libraries and are equipped with advanced amenities like smart class, computers, wi-fi connectivity etc.

According to the data released in the AISHE report, India added 70 universities totaling to 1,113 in 2020-21 from 1,043 in 2019-20. Out of these 1,113 universities, 657 are managed by the government (Central Government: 235, State Government: 422), 10 universities are Private Deemed (aided) and 446 are Private (Unaided).

The government has introduced several schemes and policies like Study in India programme which seeks to promote India as a prime hub for international students by inviting them to pursue their higher education in the country, National Education Policy (NEP 2020), Samagra Shiksha, New India Literacy Programme (NILP), etc. This article takes a critical look at India’s current standing and what it will take to achieve this ambitious vision.

Over the years, the government of India has introduced several schemes and policies to boost the higher education infrastructure as well as promote it across the world, some of them are listed below:

- New Education Policy 2020 (NEP): The policy introduced several key features specifically aimed at reforming higher education in India such as Four-year Undergraduate Programs, promotion of Indian Languages, flexible academic structure etc. The NEP 2020 also aims to increase GER in Higher Education including vocational education from 26.3% in 2018 to 50% by 2035.

- Rashtriya Uchchatar Shiksha Abhiyan (RUSA): Launched in 2013, the scheme focused on providing strategic funding to higher educational institutions and improving the overall quality of education and infrastructure. The objective of the scheme includes creating new academic institutions, expanding and upgrading the existing ones and developing institutions that are self-reliant in terms of quality education.

- The National Institutional Ranking Framework (NIRF): Approved in 2015, the framework outlines a methodology to rank institutions across the country. The parameters broadly cover Teaching, Learning and Resources, Research and Professional Practices, Graduation Outcomes, Outreach and Inclusivity and Perception.

- Study In India Program: Launched in 2018, the programme seeks to endorse India as a prime education hub for international students by inviting them to pursue their higher education in the country. It encourages international students to explore valuable educational opportunities enabled by the top Indian universities.

- Setting up of Foreign Universities in India: As per the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020, the University Grants Commission (UGC) has recently given its nod for establishing campuses of the top 100 QS-ranking foreign universities in India. This development is seen as a positive step for students, as it offers them the chance to pursue their higher education at their preferred institutions without having to move to another country.

Identifying the gaps

Despite India’s vast university ecosystem and oft cited potential, its current standing in the global higher education space is quite low. According to Project Atlas, over 5.6 million students opted to study abroad in 2020, a figure that is projected to reach nearly 8 million by 2025. The US leads well above the others in this arena, with an international student population of 1.1 million, followed by the UK (551,495) and Canada (503,270). Spain ranks last among the top 10 with an international student population of 125,675. The top source countries for the US are China, India and South Korea.

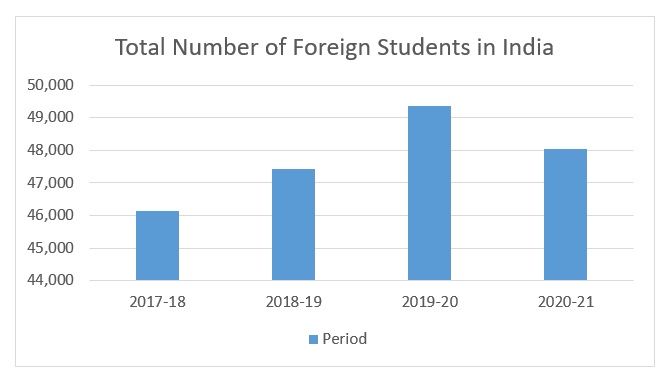

As per the AISHE 2020-21 report, the total number of foreign students enrolled in higher education in India is 48,035, recording a 2.6% drop from 49,348 in 2019-20. The enrolled foreign students came from 163 different countries. The highest share of foreign students was from Nepal (28.26%), Afghanistan (8.49%), Bangladesh (5.72%), Bhutan (3.8%), Sudan (3.33%) and the United States (5.12%).

India is also the world’s second-largest source of international students after China. According to the 2022 data released by MEA, over 1,324,954 students are studying abroad. Countries where Indian students are studying include the US (465,791), UAE (164,000) and Australia (100,009).

Source: All India Survey for Higher Education (AISHE)

While India has a competitive education ecosystem and hosts various study programs for international students, it does not figure in the league of best universities and colleges. According to Times Higher Education (THE) World University Rankings 2022, not a single Indian university is listed in the top 200 global league table. While Indian Institute of Science, Bengaluru, and Indian Institute of Technology Ropar were placed in the top 400, the top seven Indian Institutes of Technology, including the ones at Delhi, Mumbai, Chennai and Kanpur, did not participate in THE rankings for the second consecutive year as they are not convinced with the ranking methodology.

However, there are silver linings too. For instance, Indian Institute of Technology Bombay (IIT-B) has secured a place in the top 150 list of the QS World University Rankings (WUR), excelling in the metrics of employment reputation and citation per faculty.

According to various reports, there are various factors holding Indian universities back:

- Firstly, due to the large number of universities in the country, only a few of them come close to receiving the level of government funding provided to universities worldwide. Moreover, the amount of funding allocated to them is often inadequate, sparse and delayed, which has resulted in a shortage of infrastructure, equipment and resources which in turn affects the quality of education and research.

- Another field which hampers the growth of the education ecosystem is the lack of an International Research Network. Industry-academia interface in research needs to be strengthened significantly. Although some Indian universities have started collaborating with international universities to improve their research output and international rankings, a slight increase in the number of joint research projects, exchange programmes and conferences has been observed.

- The course curriculum has been cited as non-adherent to sector requirements. Several universities still follow traditional teaching methods and have not adapted to the changing needs of the modern world. This has resulted in a gap between the skills required by the industry and the skills that students possess when they graduate.

- Indian universities, accustomed to adhering to UGC and AICTE guidelines, find it challenging to meet parameters that evaluate global reputation like global diversity, international faculty, international students, research intensity, and the involvement of professors in research, among other factors.

Paving the road ahead

In an interaction hosted by IBT, some leading academicians from prominent institutes shared their views on how India can be made a higher education hub and also discussed how the ecosystem is evolving through a holistic stakeholder approach. One of the primary tools for this is promotion. Dr Vivek Suneja, Dean, Faculty of Management Studies (FMS), opined that just like every sector has champions like Wipro and Infosys for IT, the Indian higher education ecosystem also has champions like the IITs, IISc, IIMs and FMS. At least these champions must do well, and for that we need a targeted promotion strategy. He feels that there needs to be more promotion among countries in the Middle East, where there is high per capita income, and also markets like Southeast Asia and African Union that are low hanging fruits.

The virtual world, of course, offers tremendous possibilities post-pandemic. While online education does not have the same efficacy as classroom learning, Dr Suneja is confident that it can play a complementary role. This can be especially true where Indian institutes are collaborating with foreign universities for faculty exchange programmes. Sending students to foreign locations may become prohibitively costly at times, but online mode can address that challenge.

Praveen Kumar Sayyaparaju – Head – Education, Swami Vivekananda Youth Movement (SVYM) and member of NEP 2020 Implementation Task Force – Govt of Karnataka, questions the very basis of some of the rankings and feels they are misleading. Recalling his own student years in IIT Madras, he feels that he got everything he needed for his career progress. He argued, for instance, that the university rankings are very focused on the alumni and research, but not much weightage is given to the peer group. Contrarily, he feels that students learn much more in our dorm rooms and cafeteria’s than the classrooms.

On the aspect of research and interdisciplinary research, the government also rolled out another draft policy that is to be adapted – the Science, Technology and Innovation Policy. There is a Chapter 4, which focuses exclusively on research. It recognizes that we could have done much better in research and that interdisciplinary research is the way forward. Also, the government recognizes that our research should focus more on core priority areas of our country like energy, environment, agriculture, water, health and so on. Indians are very good at the foundational level and at the secondary level, but somehow, according to Mr Sayyaparaju, we are letting others set the narrative.

On building the research and education ecosystem in India, he adds, “While that is true by quantum or by volume government funding isn’t much, government share in funding and research in India is way higher than any other developed economy because there, funding for research from the industry also plays a big role. So, we should also look into the aspect of how the industry- academic institutions connect can be enhanced.”

Professor Sanjeev Sambandhan from IISc believes it is all about returning your focus to the basics – good research and the second is good teaching. Research needs to do something that is extremely interesting scientifically- an interesting theoretical problem or some fundamental aspect of nature that you’re trying to study or something that is extremely socially relevant. For him, impact is not the number associated with journals or rankings, but advancing the knowledge of humankind by solving an interesting problem or maing the life of some community easier. Teaching, on the other hand, is to communicate everything that you know in a very lucid manner to the students who are coming in, so that they appreciate and they actually learn and develop skills. The two in tandem help the image of the university grow, as positive feedback kicks in. It is an upward spiral after that.

To some extent government support is necessary, but let us say you have solved some socially relevant problem that should lead to technology translation and which in turn generates revenue, knowledge and employment and sort of strengthens the industrial base of the country. It also brings in revenue for your research. This ecosystem, if it is very well established, helps you to do interesting research and also fund it through the outcomes of your research. If this ecosystem is built then you will have an exponential growth in your higher education ecosystem.

The elephant in the room has always been the pace at which higher education can keep up with the changes in the market, especially in the current context of AI. Dr Buddha Chandrashekhar, Chief Coordinating Officer, AICTE recalls how, in the 18th and 19th centuries, India was a Vishwaguru and students from across the world used to visit Indian universities to study. In those days, we used to teach 64 different learning methodologies including understanding nature, trees, plants etc. We used to cover every aspect of the human life. But slowly the teaching methodologies have changed with Industrialization and the focal point of attention shifted to the West.

Dr Chandrashekhar is confident, however, that the NEP 2020 is helping Indian education ecosystem to adopt global standards by focusing on various content types including AR, VR and MR. We are even utilizing the advanced technologies of digital training. To improve digital infrastructure, India is starting something called National Educational Technology Forum (NETF) – an educational technology forum which basically accommodates and creates a digital infrastructure ecosystem for all our educational institutions and makes them industry ready, innovation ready, research ready and skill centered.

He talked about today’s real life scenario, when a company like Google will say, “I am okay with whatever qualification you have but your skill is what matters. I think the education is slowly shifting towards a skill based education. We are trying to accommodate and provide such kind of a digital infrastructure so that we will again gain that momentum back and the students from various countries will come back to our country to study.” India is also slowly adopting virtual laboratories and very advanced technologies to attract the domestic as well as international students. It has also upgraded our credit system so that any course you do, the credit you get in India is equivalent to the global credit framework. So foreign students who come to India to do a short-term courses will get an equal credits of the course that he/she is doing in any other country but at a lesser price.

Another major problem is that the faculty is repeatedly entering the data in order to get approval or accreditation or NIRF rankings. Now, a framework is being added wherein students enter this data only once, so that they will get 95% of the time to focus on teaching and learning. He further adds, “To boost digitisation in higher education, we have started utilizing advanced technologies as we are coming up with Education Ecosystem Registry (EER) which creates Aadhaar for Education. For every student, an organization will be able to track the performance based on one unique ID. With this tracking, we will know if a student is interested in research, innovation, startup or entrepreneurship and can guide the student for further studies.”

The remarkable insights that the IBT team gained from the session indicate that the higher education ecosystem in India is a multifaceted and evolving landscape. A lot of interesting initiatives are being undertaken in the realm of research, better teaching outcomes, foreign collaboration, skill development, improved learning environments and support for career planning. Widespread adoption of such proactive measures will certainly be beneficial in improving India’s stature and attract greater numbers as well as diversity to students visiting India. At the same time, it will be important to address some major gaps that include funding for research and aggressive promotion of leading Indian institutes in key markets, at least in the short term.

Leave a comment