Supply Chain Disruptions: A Revival of ‘Make in India’?

Prof Manoj Pant and Samridhi Bimal argue that post-COVID economic recovery will be largely determined by a viable manufacturing sector which is in desperate need of technological advancements. If India is looking at becoming the next major supply chain hub and realising the Make in India vision, greater liberalization of FDI policies needs to be complemented with greater liberalization of trade policies.

A defining feature of the pre-COVID world was the globalization of supply chains. The progressive liberalization of cross-border trade in goods and services, advent of fourth industrial revolution bringing significant advancements to information technology and production processes, and reduction in transport and logistics costs enabled multinational firms to fragment their production processes geographically across borders. The emergence of global production networks propelled the rapid increase in cross-border FDI flows and a rising trade in raw materials and intermediate goods.

With the outbreak of the Coronavirus pandemic, the world is engulfed with a threat of a catastrophic spiral of protectionism and subsequent disintegration. The future of global supply chains is uncertain. A number of multinational firms that once thrived on the cost efficiency of Chinese production are now planning to move their base out of China and explore alternate hubs of production and manufacturing. The focus is now on diversifying and de-risking the supply chains.

The COVID-19 crisis has presented an opportunity for India to become the epicentre of multinational supply chains. This opportunity is in line with the much talked about Make in India initiative, which was launched in 2014 with the goal of making India a global manufacturing hub, by encouraging both multinational as well as domestic companies to manufacture their products within the country. Whether India will be able to leverage the COVID crisis and transform the vision of Make in India into a reality will largely depend on its foreign trade and investment policies.

Technology is the key to success of ‘Make in India’

The success of the Make in India initiative hinges on the revival of the manufacturing sector. It is a common fact now that India’s manufacturing sector growth has remained sluggish with the sector share to GDP stagnating at about 16-17% since the last few years. Irrespective of several reforms pursued by the government, the performance of the manufacturing sector has continued to remain bleak. The problem is intrinsic and has to do with the low levels of technological capabilities of the Indian manufacturing sector. This is also reflected in our export basket, which comprises primarily of primary and low-technology goods.

Technology is the key ingredient that India needs for revolutionizing its production processes, modernizing the manufacturing sector and realizing the vision of Make in India. Trade and FDI activity of multinational firms are the two most natural channels for the international diffusion of technology. In order to formulate sound policies for enabling technology transfer and technological up-gradation of the manufacturing sector, it is essential to understand the close relationship between trade and FDI.

Trade and FDI are Complementary

At the centre of this relationship are the Multinational Enterprises (MNEs) whose operations span several countries and their presence in an economy is reflected in FDI figures. Contrary to popular belief, trade and FDI are two complementary (not alternative) ways for MNEs to access the foreign market. The organization of production within MNEs often takes the form of vertical specialization, wherein the production process is fragmented geographically across borders, locating each stage in the country where that part of the process can be done most efficiently.

MNEs link all these stages through trade and supply goods and services to their buyers worldwide. This type of trade, which is conducted between parent companies and their affiliates or among the affiliates is called ‘intra-firm trade’ and is different from international trade conducted among unrelated parties.

The expansion of activities of MNEs and the advent of GVCs have intensified the value of intra-firm trade flows. As per UNCTAD estimates, about 80% of global trade is being conducted within the ambit of MNEs. It is imperative to understand that this trade takes place only when MNEs invest abroad. So, FDI is a channel through which trade flows expand.

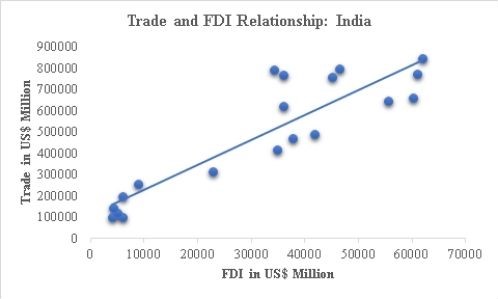

In the case of India as well, simply eyeballing the relationship between trade and FDI makes our point clear. The upward sloping trend line indicates that there is almost a one-to-one positive correlation between trade and FDI flows.

Source: Drawn by the authors based on data from RBI Handbook of Statistics on Indian Economy

(2019)

Going Ahead

To conclude, post-COVID economic recovery will be largely determined by a viable manufacturing sector which is in desperate need of technological advancements. Technology can be acquired slowly through learning from technology leaders who are nothing but foreign multinational enterprises which bring in FDI to a country. In this process, imports of certain raw materials and intermediate goods will inevitably rise. However, if India is looking at becoming the next major supply chain hub, it has to be prepared that products at different stages of value-added will be imported and exported multiple times. Any form of protectionist trade policies must be resisted at this time. In fact, greater liberalization of FDI policies needs to be complemented with greater liberalization of trade policies.

The emerging global order necessitates a re-think in the way the government formulates its foreign trade and investment policy. For long, policymakers have addressed trade and FDI on separate tracks, but this needs to change. We need to acknowledge the close inter-linkages between the two and take a holistic approach to trade and investment policymaking. There is a need to review our existing institutional mechanisms governing trade and FDI policymaking and revise them to ensure harmonized, integrated and inclusive policies. Policy coherence between trade and FDI policies would ensure that they are mutually reinforcing in support of India’s vision of becoming a global manufacturing hub.

Prof Manoj Pant is an Indian expert in International Trade. He is the Director of Indian Institute of Foreign Trade, since August 2017. Previously, he was a full-time professor at the Centre for International Trade and Development, Jawaharlal Nehru University, where he taught international trade theory.

Samridhi Bimal is a trade economist with nine years of research expertise on international trade and trade policy issues related to the WTO, regional trading agreements and domestic trade policies. She has worked extensively on South- and South-East Asia on a wide array of issues including trade, investment, transport facilitation, non-tariff barriers and informal trade. Her research areas of interest include international trade, development policy and regional economics. She holds a PhD in Economics from the Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU), New Delhi.

Views expressed are personal.

Excellent piece, written with great clarity.