Indian agriculture’s investment riddle

• India confronts eclectic challenges in becoming an attractive partner in agricultural investments. The biggest challenge is that the quantum of public investment itself leaves much to be desired.

• Since the past eight years, India’s public agriculture investment is hovering around 5-6% to total public investment made. Corresponding figures in developed nations are recorded at between 15-20%, and in some countries like in the US, it’s even higher.

• Based on CATR analysis using national input output table, India’s primary agriculture’s contribution as an input into its own output fell to 12.9% from 16.5%. Agriculture’s contribution to processed food and beverages also fell to 31.9%.

• The backward linkages of primary agriculture due to processed food and beverages remained significantly low. This could imply continued weakness in growth of primary agriculture.

Image credit: Development News

India’s agricultural and food processing industries are growing steadily, and so are exports from these sectors. The country’s involvement in global value chains may not have grown significantly, but it has considerable potential to export these products, which constitute a high share (more than 70%) of global exports. Rashmi Banga (2016) opined that by increasing exports of manufactured products through global value chains, India can become more competitive, upgrade workers’ skills and generate employment generation. However, in the case of agriculture, India confronts several challenges towards becoming an attractive partner in agricultural investments. The biggest challenge is that public investment in Indian agriculture leaves much to be desired.

Liberalization of the economy was expected to result in higher investment and growth in agriculture, induced by favourable terms of trade. It was expected that the gains in terms of trade would increase investment in agriculture, but actually the non-agriculture sector benefited more. So the expectations did not materialize. Agricultural growth slackened and investment in agriculture, particularly on public account, relatively did not surge.

Public investment is especially important for funding agricultural R&D where markets fail because of the difficulty of appropriating the benefits. Many developed countries like US, Canada, countries of EU are characterised by significantly higher government investments in the agriculture sector as compared to India. Since the past eight years, India’s public agriculture investment is hovering at about 5-6% of total public investment made. Corresponding figures in developed nations range between 15- 20%, and in some countries like the US, it’s even higher.

Public investment in agriculture as a % of total public investments in India

According to the figure, public investments in agriculture remained nearly static over the years, signalling that this sector is neglected or rather left isolated to grow and expand on its own. Economists argue that there has been an urban bias in the allocation of public investment as well as mis-investment within agriculture. Further if we look at the backward linkage of Indian agriculture by using national input output table data, we can corroborate the argument.

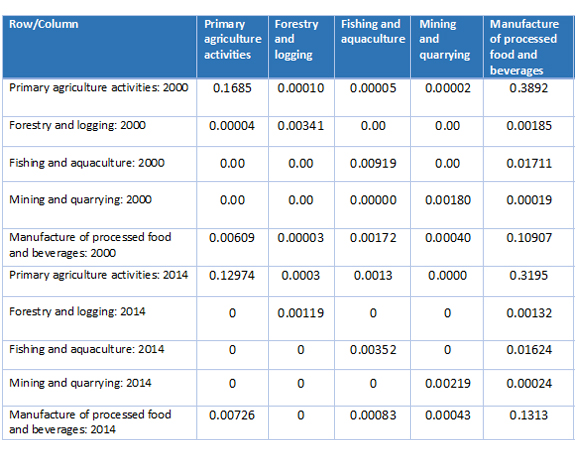

Estimates based on latest national input output table (NIOT) show some change in the technology matrix’s structure. India’s primary agriculture’s contribution as an input into its own output fell to 12.9% from 16.5%. Agriculture’s contribution to processed food and beverages also fell, to 31.9%. The only improvement was in processed food and beverages’ contribution to its own output, increasing from 10.9% in 2000 to 13.13% in 2014.

Analysis also reveals that there are no significant linkages between primary economic agricultural activities and allied activities viz. forestry, fishing, and mining. The backward production linkages of the food-and-beverage industry with agriculture have been modest, and the magnitude of intra-industry linkage has increased, which may be explained by the stagnating growth rate of agriculture and allied activities of 3-4% per year, compared to the relatively higher and increasing growth rate in the processed-food industry.

But the backward linkage of primary agriculture with processed food and beverage remained significantly low. To elaborate this, the latest figure suggests that the final output generated by primary agriculture sector due to processed F&B sector is 0.007 units or 0.7% which is extremely low. If this is not addressed, the pace of bolstering primary agriculture will remain weak due to its insignificant backward linkage.

Table: India’s technology matrix as per NIOT

Source: CATR calculations from National Input-Output Table (NIOT)

We now move to analyse India’s Leontief inverse coefficients within agriculture and allied sectors. The Leontief inverse matrix (I-A)-1 provides a set of disaggregated multipliers that are recognized as more precise and sensitive than Keynesian multipliers for studies of detailed economic impacts. The Leontief inverse matrix ─ a multiplier matrix ─ takes into account that the total effect on output will vary, depending on which sectors are affected by changes in final demand.

The total output multiplier for a sector measures the sum of direct and indirect inputs needed from all sectors to fulfil a given sector’s final demand requirements. Therefore, once the initial change in final demand is known, the values of all inputs and outputs needed to fulfill it can be determined.

During 2000 and 2014, the output multipliers of direct input required were moderate for primary agriculture, at 1.21 and 1.155, and for processed food and beverages, at 1.129 and 1.158. The output multipliers of indirect requirements were nearly zero for almost all the sectors within agriculture, except for the output multiplier in processed food provided by primary agriculture. We find hardly any structural change in the output multipliers during this period. In fact, the size of direct output multipliers decreased in all four sectors under primary activities. The only exception was in processed food and beverages, where values increased marginally, from 1.1288 to 1.18.

Economic studies find that public investments made in agricultural R&D and the application of industrial inputs in agriculture have been major factors in the successful transition from resource-dependent to productivity-led agricultural growth. National public investments in agricultural R&D, along with technology spillovers from other countries and the private sector, are significant sources of new technology driving growth in agriculture’s total factor of productivity. Farmer education, liberalized trade, and changes in agricultural structure also contribute to greater agricultural efficiency and productivity. India thus, need to pull its socks in a similar direction to escalate the contribution from agriculture sector. Proliferation of public investment in agriculture sector is critical for doubling farm’s income as well.

Leave a comment